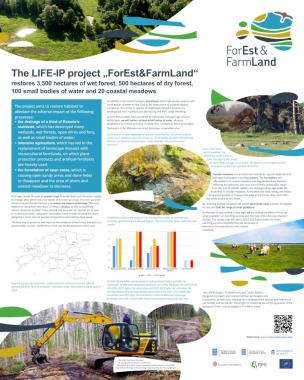

Based on the wet forest habitat action plan (summary available in English) and dry forest habitat action plan (both compiled in the project), Estonian State Forest Management Centre restores 3,500 hectares of deciduous swamp forests and 500 hectares of dry forests during the project. The wet areas to be restored are selected by the forestry working group from the University of Tartu and the dry areas to be restored are selected by the University of Life Sciences.

Although the aim of restoration is usually to improve the condition of the area, there are also exceptions: if the nature conservation value of a previously drained protected bog woodland is constantly declining due to a functioning drainage system, then restoration activities (closure of the drainage system) are necessary simply to maintain the condition of the area.

The forestry team from the University of Tartu selected the areas in need of restoration in several stages:

- initially, a pre-selection of core areas with deciduous swamp forests within Natura sites was carried out as a geo-information request;

- areas with a visually higher drainage impact were then selected from this set, where the closure of drainage ditches could improve the quality of wet deciduous forests;

- in the second stage, areas with a surface area of less than 20 hectares were removed from the generated sample: as a result, 64 areas were selected (with a total area of about 20,000 ha, the estimated area per site being 50–1,000 hectares per area);

- in the third stage, 12 factors related to these areas were assessed, such as the proportion of forest stands in the total area, the proportion of deciduous forests over 50 years of age out of all deciduous forests, the compactness of the drainage system to be closed, land ownership and protection-related questions, and the proportion of private land in the limited management zone. Existing factors could provide both positive (contributing to the success of the restoration) and negative points (factors limiting the success of the restoration or the risk of destruction of already existing values);

- in the fourth stage, the main problems involving the fields were clarified – the experts familiarised themselves with the past history of the areas, covered the wider surroundings, mapped the sites of protected bird species that may be sensitive to disturbances, and identified the form of ownership and protection status of the areas.

This left 17 areas for screening, which, in turn, are divided into seven priority groups.

The project restores 7 areas:

- Peterna-Laashoone (1480 ha) in Alam-Pedja nature reserve

- Laulaste (414 ha) in Laulaste nature reserve

- Ohepalu (363 ha) in Ohepalu nature reserve

- Karuskose (274 ha) in Soomaa national park

- Pihla-Kaibaldi (529 ha) in Hiiumaa island

- Tudusoo (582 ha) in Tudusoo nature reserve

In the second half of 2022 Tallinn University’s wet forests working group began to perform preliminary monitoring of the first restauration areas. State Forest Management Centre has prepared the restoration projects and organised public consultations during 2023-2025.

Peterna-Laashoone restauration work is the first to be finalysed in November 2025.

The restoration area of Peterna-Laashoone (1480 ha) is located in the Alam-Pedja Nature Reserve, and it contains medium or heavily drained fen and carr forests. On the banks of the Pedja River there are still some riparian-carr forests, which contain large stumps and lush herbaceous plants, and small but mighty floodplain forests of old alder, aspen and linden trees.

The name Laashoone (laas = glass) means glass factory. Due to the large timber supply, this forest area between the Pedja River and the Emajõgi River was chosen as the location of the Meleski glass factory, the second largest glass factory in Tsarist Russia, towards the end of the 18th century. Making glass requires high temperatures and a lot of energy, which needs a lot of timber. This is why there are no primary forests in the Meleski and Peterna-Laashoone areas, as these areas have been cut many times over the past 300 years. The last major clearings, during which wider and deeper ditches were made, date back to the 1960s and 1970s, and much of the forest qualifies as a full-drained swamp forest.

After raising the water level, a slow return of marshy plants should begin and spruce should start to be replaced with birch (either sown or planted there).

The results of the restoration activities at the Peterna-Laashoone area cannot be seen quickly – it may take several generations to recover this area’s rich biota - but the rich wildlife of the area and the forests affected by the Pedja and Emajõgi Rivers deserve to be in a better condition.

In the Ohepalu area (363 ha) a lush, and in some places broad-leaved, forest has developed on the eskers next to the Udriku lakes, on the site of former wooded meadows. Between the eskers and to the south-west and west of them, on the Kaansoo side, fen woodlands alternate with fen clearings and reforested clear cut areas. The vegetation is lush and species-rich, with abundant orchids – the lesser and greater butterfly-orchid, the marsh helleborine and the early marsh-orchid. Drainage impacts are substantial around Kaanijärv Lake and the old drainage ditches, where full-drained swamp forests alternate with fen woodlands impacted by draining. Drainage impacts are more pronounced in the area of the Kaanjärve-Pala stream ditch and Pala road.

Unlike other Ohepalu areas restored by the Estonian Fund for Nature in the framework of the LIFE project ‘Conservation and restoration of mire habitats’, the water regime of Ohepalu 2 was not restored and it is commendable that the last section of Ohepalu's biodiverse wetland will return to its natural state.

Photo 1: The main drainage facility of Ohepalu restoration area is the ditch flowing into the Pala stream from Lake Kaanjärv. With the closure of ditches, the condition of forests around the ditch will improve, and water levels in the lakes will also rise.

Photo: The flood-meadow on the Pedja riverside is a habitat for the great snipe, a bird of European importance, and is a regularly mowed flood-meadow. When raising the water level in the Peterna-Laashoone forest, one must also take into account the accessibility of flood-meadows — a tractor must be able to mow them in summer.

Photos made by Laimi Truus.

Restoration process

The main goal of the restoration of a wet forest habitat is to reduce the impact of drainage, i.e. to close the ditches. Usually, one dam is not enough to close a ditch, as the high water would simply wash it away during wet periods. Therefore, several dams will be built on the ditch, or the ditch will be completely closed along its entire length using soil.

Soil works are usually carried out with an excavator. In order for such a large machine to move, it is usually necessary to remove trees from the targets along the ditch. This is one of the negative factors involved in restoration. Ditches can also be closed manually during the work, but it is difficult to find people to perform such large-scale shovel work. In certain instances, however, this has been done.

During the course of restoration or due to the changes that followed, the existing natural values of the area (rare species or established forest communities with old trees) may be damaged. Restoration is quite costly and leaves a significant climate footprint when using large machines. Therefore, restoration work is not carried out lightly; instead, areas are sought that have suffered damage from human activity to such an extent that natural restoration would take a long time.

Cost-effectiveness must also be monitored. For example, in a formed drained peatland forest, bog processes do not recover within a reasonable time, and in the case of elevated water levels, a large part of the established forest stand will probably be destroyed. Therefore, priority should be given in restoration to areas where the value of the wet forest habitat can be increased more effectively.

In both wet and dry forest habitats, restoration activities may include the thinning of forest stands and the shaping of a more natural composition of tree species, as well as the generation of dead wood. For example, in the case of dry forest habitats, such as forested dunes and coniferous forests located on eskers, formative cutting may be given consideration to preserve the habitats of the endangered species associated with them. Activities that promote the development of these habitats, such as weak surface fires or temporary light grazing, could also be maintained.

In most cases, the best way to maintain and improve the condition of a habitat is for people to not interfere any further with the natural development of the area.

Background reading

- We are restoring the traditional, yet so mysterious woodland habitats (Voldemar Rannap, project manager, Kaidi Tingas, project communication manager)

- Reducing CO2 emissions from land: Restoring wetlands or drainage systems? (Estonian Public broadcasting 2022)

- Estonia planning to restore 25,000 hectares of marshland by 2050 (Estonian Public Broadcast 2024)

- Focal species in wetland restoration (dissertation by Elin Soomets, Tartu University)